Project details

Included in the exhibition All Due Respect alongside artists Mequitta Ahuja, LaToya Hobbs, and Cindy Cheng

https://artbma.org/exhibition/all-due-respect/

Wenesday, February 16, 2022: Lasting Legacies with moderator Dr. Leslie King-Hammond

https://artbma.org/event/bma-violet-hour-lasting-legacies/

Forget-me-not and Spolia at the Baltimore Museum of Art

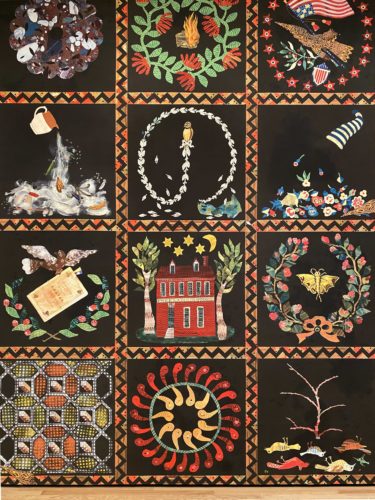

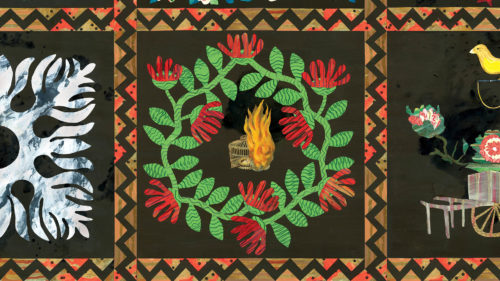

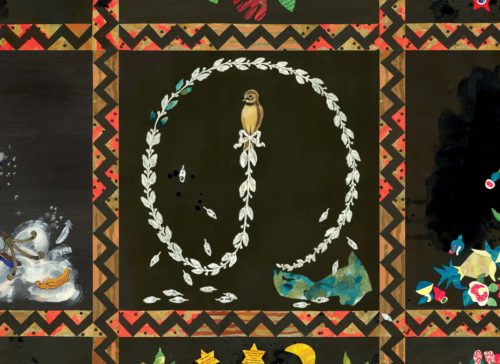

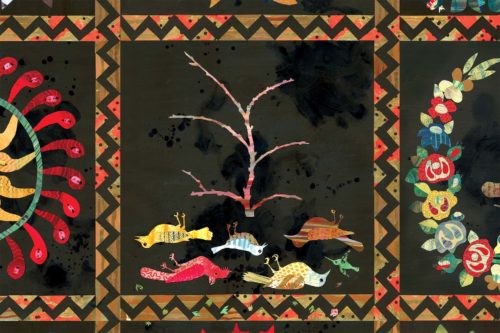

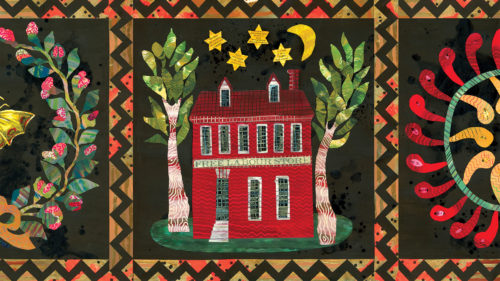

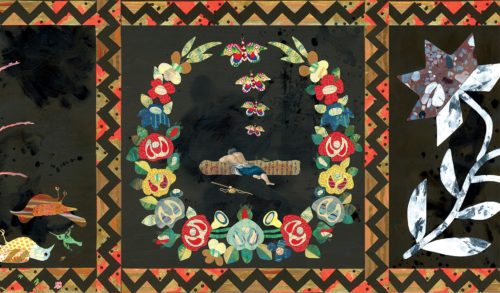

This project’s point of departure was the Baltimore album quilts and painted furniture from the Baltimore Museum of Art collection which were produced by named and anonymous craftspeople from 1800 -1850. The piece consists of 22 repeating quilt blocks made from acrylic paintings on paper and six round (tondo) paintings displayed adjacent to an early 19th century mirror and Morris suite chair from the BMA collection. The works directly engage the visual language of the BMA’s painted furniture and the design language and themes of the BAQs.

The period’s painted furniture and quilts demonstrate interest in local flora and fauna and the repurposing of mythic symbols from classical antiquity. Commonalities such as neoclassical motifs and local landmarks exist in their designs. My work subverts these typical arrangements. For instance, garlands featuring a ship or bible now include moments from Baltimore history and the BMA collection, merging both history and museum object. I address the limited speech of the source objects whose themes became possibilities for interpretation: birds were liberated or expired; grief and despair emerged in the lively designs; an upside-down flag signaled failed promises and lesser-known Baltimoreans were recalled.

Social alliances are inherent to the source objects as is the position of those who made or commissioned them. These alliances, the relationship to archeological discovery and the buttressing of the young American political vision through references to ancient forms, are well-documented in Federalist fine art and design literature. Less well-known is the free or enslaved status of those who likely assisted in producing these quilts and furniture. I grapple with the unreliable myths of domestic virtue and harmonious citizenship often ascribed to this material— disrupting the dominant narrative of American exceptionalism by quoting imagery to examine its claims to truth and power.

The means by which Baltimore furniture and quilts were deemed valuable enough to preserve in the BMA’s collection concerned me, thus necessitating navigating their monumentality as museum acquisitions. While working with museum staff, I began to understand these objects’ connections to their historical context and as sites of fantasy for connoisseurs. A typical conscription asserts these objects were made in and of their time, depicting the personal expression of makers and commissioners through aspirational pictorial statements. This interpretation expands to fantasies about the past and those who lived in it, which are in a limited way knowable through material and archival sources. But the past is mostly inscrutable and suggestive gaps emerge that lend themselves to interpretation. I examine these gaps and the pretense of the objects’ accessibility—interposing what I see within and against their historiography and that of Baltimore itself.

Commemorative landscapes appear frequently in these objects as patchwork designs of city monuments and plantations—historic enslavement sites that have mostly been built over through racist redlining and divestment, yet vestiges remain in sites named for or by former ‘masters.’ Relevant for me is my proximity to the vestigial landscape (my house sits two blocks from a former plantation known as Vineyard) and my positionality as a white middle-class woman (a descendant of enslavers), within the ongoing apartheid conditions in the city. Researching during a pandemic, I discovered elite Baltimoreans whose country houses shielded them from city plagues 200 years ago. Furniture painted with rural plantations alluded to an always-available escape— feeding my awareness of how my own notions of escapism shaped my responses to these objects.

Instead of directly linking the past with today’s Baltimore, however, I explore alternative memory modes to imagine the mundanities of an early-1800s Baltimore in lieu of a readily accessible city of the past.

Additional Support:

The artist would like to thank the staff of the Baltimore Museum of Art for support in making this project possible. Leila Grothe, BMA Associate Curator of Contemporary Art, organized this exhibition. Studio assistance was provided by Ladan Savar. Research support was provided via the Maker-Creator Fellowship at the Winterthur Museum in Delaware. Additional support provided by the Joan Mitchell Foundation.